Introduction

Knee ligament injuries are far from being anecdotal, representing between 20 and 40% of sports injuries affecting this crucial joint. In orthopedic medicine, these problems pose a significant challenge by disrupting joint stability and function. The causes are often linked to sports trauma, accidents or sudden movements, with consequences ranging from moderate discomfort to severe impacts on quality of life. Understanding the complexity of knee ligaments, the risk factors associated with their deterioration, and advances in diagnostic and treatment methods is essential to address this orthopedic problem.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are the main protagonists in this injury story. The injuries are not limited to a single ligament; the ACL and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) provide rotational stability, while the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and MCL provide lateral stability. When one is affected, other knee structures, such as the menisci and articular cartilage, also come into play.

Ligament injuries usually occur traumatically, involving forced rotation, a direct blow, or both. The result is often a popping noise, followed by swelling and instability when weight-bearing the affected limb. It’s a scenario that plays out frequently on sports fields and in other settings.

However, beyond the dramatization of these incidents, this text also explores more pragmatic aspects. It highlights the crucial importance of prevention, early diagnosis and therapeutic innovation to optimize recovery. By understanding the complexity of knee ligament injuries, the medical community can develop more effective strategies to anticipate, treat and rehabilitate these injuries. It is a call to action, highlighting the need for pragmatic medical approaches to address this widespread and often debilitating problem.

Knee ligaments

| Impact force | Lateral | Medial | Posterior | Previous |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial collateral ligament | Sprain | |||

| Lateral collateral ligament | Sprain | |||

| ACL | Sprain | Sprain | ||

| Posterior cruciate ligament | Sprain | Sprain |

Causes of knee ligament injury

- Direct trauma:

- Mechanism: A direct impact on the knee, often seen in sports accidents, falls or collisions.

- Excessive knee twisting:

- Mechanism: Sudden, excessive twisting of the knee, usually associated with sudden changes in direction or pivoting movements.

- Hyperextension:

- Mechanism: Excessive stretching of the knee beyond its normal range of motion, often seen during falls or uncontrolled movements.

- Forced knee flexion:

- Mechanism: Forced flexion of the knee beyond its normal range, which can occur during landings from jumps or excessive bending movements.

- Improper landing after a jump:

- Mechanism: Improper landing after a jump, especially if the person lands with the knee misaligned or hyperextended.

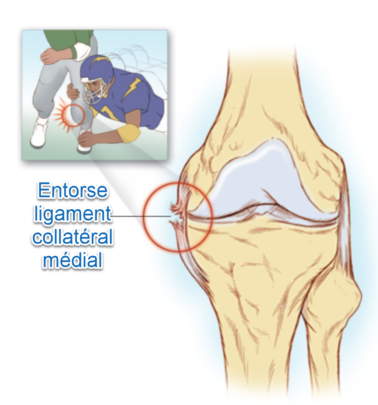

- Lateral knee collision:

- Mechanism: A lateral force applied to the knee, often encountered in sports such as football or rugby, where physical contact is frequent.

- Abrupt change of direction:

- Mechanism: Rapid, abrupt movements that involve a change of direction, such as those observed in certain sports such as basketball or soccer.

- Non-traumatic injuries (chronic wear):

- Mechanism: The gradual wear and tear of ligaments due to repetitive motion or overuse, which can lead to deterioration over time.

- Degenerative lesions:

- Mechanism: Age-related degenerative changes that gradually weaken the knee ligaments.

Symptoms of knee ligament injury

- Pain: Sudden or progressive pain in the knee, which may be localized or spread to other parts of the leg.

- Swelling: Swelling around the knee caused by fluid buildup in the injured area.

- Hematoma: Bruising or discolored spots around the knee may develop due to internal bleeding.

- Feeling unsteady: Some individuals may feel a feeling of weakness or instability in the knee, as if they are unable to support their body weight.

- Limited mobility: The ability to fully bend or extend the knee may be reduced due to pain and swelling.

- Crepitation: Some patients sometimes report a crepitating or cracking sensation when they move their knee.

- Difficulty bearing weight: The ability to bear body weight on the affected knee may be compromised, particularly when walking or weight-bearing.

- Heat: The area around the knee may feel hot to the touch due to inflammation.

Terrible Triad (O’Donahue’s)

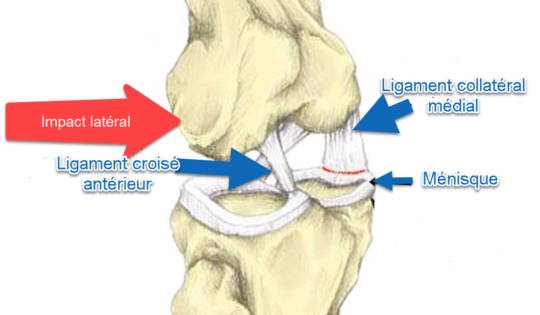

The “terrible triad”, also known as the “O’Donahue triad”, is a term used in sports medicine to describe a particularly serious knee injury. This triad generally consists of three major injuries occurring simultaneously during knee trauma. The classic components of the terrible triad are:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury: The ACL is a crucial ligament that maintains the stability of the knee by preventing the tibia from sliding forward relative to the femur. An ACL tear is commonly seen in the terrible triad.

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury: The MCL is located on the inner side of the knee and helps prevent too much inward tilt of the knee. MCL injury is often present in the terrible triad.

- Rupture of the medial meniscus: The menisci are cartilaginous cushions located between the femur and the tibia. In the terrible triad, the medial meniscus, located on the inner side of the knee, can be damaged, usually by a twisting mechanism.

This combination of injuries is often associated with sports trauma, particularly in contact sports such as football or rugby. The terrible triad is considered serious due to the simultaneous nature of these three major injuries, which can lead to significant joint instability and long-term complications if not properly treated.

Diagnosis of the terrible triad is usually confirmed by imaging tests such as MRI, and treatment may involve surgery to repair damaged ligaments and meniscus, followed by intense rehabilitation to restore knee function . Managing the terrible triad requires a multidisciplinary approach involving specialists in orthopedics, physical rehabilitation and sports medicine.

Most commonly, this injury occurs as a result of significant rotational forces and lateral impact force production on the nearly or fully extended knee, when the foot is firmly planted on the ground.

Classification of sprain

- Grade I sprain:

- Mild ligament injury.

- Excessive stretching of the ligament without significant tearing.

- Typically associated with mild pain, mild swelling, and preserved joint function.

- Recovery is often rapid with proper care, such as rest, ice, compression and elevation (RICE), and rehabilitation.

- Grade II sprain:

- Moderate ligament injury.

- Partial tear of the ligament with some degree of loss of function.

- May cause greater pain, swelling and partial joint instability.

- Treatment may include RICE, temporary immobilization, physiotherapy to strengthen the muscles and restore stability.

- Grade III sprain:

- Severe ligament injury.

- Complete tear of the ligament, resulting in significant loss of joint function.

- Often associated with severe pain, significant swelling and marked instability of the joint.

- May require surgery to repair the torn ligament, followed by intensive rehabilitation.

It is important to note that the classification of sprains into grades I, II and III provides a general perspective, but each case is unique. The precise diagnosis and specific treatment plan may vary depending on several factors, including the location of the affected ligament, the presence of concomitant injuries, and the individual needs of the patient.

Safety and Prevention Tips

- Warm-up Before Stretching: Before beginning any knee ligament stretching session, devote time to a proper warm-up. Light cardiovascular activities, such as brisk walking or light jogging, increase body temperature and prepare muscles and ligaments for stretching.

- Knowledge of Personal Limits: Each individual has different physical limits. Listen to your body and respect your personal limits during stretching. Don’t force movements beyond your comfort threshold, and be aware of feelings of tightness rather than sharp pain.

- Signs of Overstretching: Learn to recognize the signs of overstretching to avoid injury. Signals such as sharp pain, a tearing sensation, or persistent discomfort should be taken seriously. If you experience these signs, stop stretching immediately.

- Gradual Progression: Avoid pushing your body beyond its immediate capabilities. Opt for a gradual progression in intensity and duration of stretching. This allows your ligaments to gradually adapt to the effort, reducing the risk of injury.

- Preliminary Dynamic Stretches: Before engaging in static stretching, consider the inclusion of prerequisite dynamic stretches. These active movements help increase joint mobility and prepare the ligaments for the more intensive work of static stretching.

- Use of Breathing Techniques: Incorporate deep, controlled breathing techniques during stretching. Regular breathing can help relax muscles and prevent excess strain on ligaments.

- Maintaining Knee Stability: When performing stretches, be sure to maintain knee stability by engaging the surrounding muscles. This protects the ligaments by preventing excessive movement.

- Hydration and Nutrition: Make sure you are well hydrated and eat a balanced diet. Adequate hydration promotes tissue flexibility, and a healthy diet helps maintain ligament strength.

- Regular Stretching: Regularity is essential. Incorporate stretching sessions into your routine consistently rather than sporadically. Consistency helps maintain flexibility and reduce the risk of injury.

- Professional Consultation: Before beginning an intensive stretching program, consult a healthcare professional, such as a physiotherapist or orthopedist, for personalized advice and recommendations tailored to your individual situation.

Stretching your knee

Here is a stretching program that aims to improve knee flexibility. Before you begin, be sure to consult a healthcare professional or trainer to ensure these exercises are suitable for your physical condition. Always listen to your body and avoid any painful stretches.

For beginners

- Stretching the quadriceps muscles:

- Stand tall, bend your knee, raising your heel toward your buttock.

- Grab your ankle with your hand on the same side.

- Hold the position for 20-30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

- Hamstring Stretch:

- Sit on the floor with one leg extended and the other bent.

- Gently lean forward, keeping your back straight.

- Hold the position for 20-30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

- Stretching the calf muscles:

- Stand facing a wall, with one leg bent forward and the other extended behind you.

- Press your hands against the wall and lean forward.

- Hold the position for 20-30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

For advanced levels

- Standing quadriceps stretch:

- Stand tall, bend your knee and grab your ankle behind you with your hand.

- Gently push your foot toward your buttock.

- Hold the position for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

- Repeat on the other side.

- Stretching the hip flexors:

- On your knees, place one foot in front of you at 90 degrees.

- Slowly move forward, keeping your back straight.

- Hold the position for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

- Repeat on the other side.

- Stretching the muscles of the back of the thigh with a strap:

- Lie on your back with your legs straight.

- Place a strap around the sole of the foot and lift the leg, keeping the knees straight.

- Hold the position for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

- Repeat on the other side.

Repeat these stretches regularly, ideally after a short warm-up session. Remember to breathe deeply during each stretch and adjust the intensity according to your comfort level. If you feel any pain, stop exercising immediately.

Strengthening the muscles around the knee is crucial to supporting the ligaments and helping to prevent injuries. Muscles play a vital role in joint stability, and muscle imbalance or weakness can increase the risk of injury to knee ligaments, such as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL). Here are some specific strengthening exercises for the knee muscles and an explanation of the relationship between muscle strengthening and injury prevention.

Strengthening Exercises for Knee Muscles

- Quadriceps Extensions:

- Sit on the floor with your legs extended in front of you.

- Raise one leg by extending the knee and hold the position.

- Alternate legs. Do 2 to 3 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions for each leg.

- Leg Press:

- Use a leg press machine or thigh press.

- Push the platform with your feet, making sure to keep your knees in line with your feet.

- Do 3 sets of 10 to 12 repetitions.

- Hip Extensions (with resistance):

- Attach a resistance band to a stationary surface.

- Tie the other end around the ankle.

- Raise the side leg against the resistance, keeping the knee straight.

- Do 2 to 3 sets of 12 to 15 repetitions on each side.

- Squats:

- Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart.

- Bend your knees as if you were going to sit, keeping your back straight.

- Do 3 sets of 12 to 15 repetitions.

- Hamstring Curls:

- Lie on your stomach with your feet attached to a hamstring curl machine.

- Bend your knees to lift the load, then slowly lower it.

- Do 2 to 3 sets of 10 to 12 repetitions.

Relationship between Muscle Strengthening and Injury Prevention:

- Joint Stabilization: Strong muscles around the knee help stabilize the joint, reducing the load on the ligaments and decreasing the risk of injury.

- Muscle Balance: An imbalance between opposing muscles (like the quadriceps and hamstrings) can increase stress on the ligaments. Balanced reinforcement helps maintain proper load distribution.

- Dynamic Control: Functional exercises, such as squats and lunges, improve dynamic control of the knee during daily and sporting activities, reducing the risk of injury.

- Prevention of Excessive Strain: Strong muscles better absorb shock and stress, reducing pressure on ligaments during activities such as running, jumping or lateral movements.

In conclusion, a targeted muscle strengthening program can play a key role in preventing knee ligament injuries by improving stability, muscular balance and dynamic control. It is important to integrate these exercises into an overall training program, taking into account individual fitness level and progressing gradually. If knee problems exist, it is advisable to consult a healthcare professional for personalized advice.

Recovery and Care

Recovery from intensive stretching is crucial to promote flexibility, reduce muscle stiffness and prevent injury. Here are some recovery techniques, including the use of ice and heat, and the importance of rest and active recovery:

- Ice :

- Ice Application: After intensive stretching, ice application can help reduce inflammation and relieve pain.

- Duration: Apply ice for 15 to 20 minutes.

- Frequency: Repeat every 1 to 2 hours for the first 48 hours.

- Heat :

- Heat application: Heat can promote blood circulation, relax muscles and improve flexibility.

- Use: Use heating pads, warm baths or hot showers.

- Duration: Apply heat for 15 to 20 minutes.

- Active Recovery:

- Light cardiovascular exercise: Light physical activity, such as walking, swimming, or cycling, can help eliminate metabolic products from stretching.

- Gentle stretches: Perform gentle stretches to maintain flexibility and prevent stiffness.

- Massage:

- Self-massage or professional massage: Massage can help relieve muscle tension and improve blood circulation.

- Compression:

- Using Compression Bandages: Light compression can help reduce swelling and support muscles.

- Nutrition and Hydration:

- Hydration: Make sure you stay well hydrated to promote cell recovery.

- Balanced diet: Nutrients, especially protein, play an important role in muscle recovery.

- Sleep :

- Adequate rest: Sleep is crucial for recovery. Make sure you get quality sleep.

- Avoid Consecutive Intensive Training:

- Rest days: Integrate rest days into your training program to allow for optimal recovery.

- Listen to Your Body:

- Individual Response: Each person responds differently to training and recovery. Listen to your body and adjust your program accordingly.

- Consult a Health Professional:

- For persistent pain: If you experience persistent pain despite recovery techniques, consult a healthcare professional.

Conclusion

A deep understanding of knee ligament injuries is essential not only for the treatment but also for the prevention of these common yet potentially debilitating issues. By familiarizing oneself with the causes, symptoms, and risk factors, individuals can take a proactive approach to safeguarding their knee health. This includes engaging in proper conditioning exercises, practicing safe movement techniques, and seeking early medical intervention when necessary. For osteopaths, such knowledge is integral in guiding patients through tailored rehabilitation programs that focus on restoring function, improving mobility, and ultimately enhancing the quality of life.

Moreover, the emphasis on prevention cannot be overstated. Preventative strategies, when implemented effectively, significantly reduce the likelihood of knee injuries and support the long-term health and stability of the joints. Whether you’re an athlete, a weekend warrior, or simply someone who values an active lifestyle, understanding and protecting your knees is vital for maintaining overall physical well-being. As the field of osteopathy continues to evolve, staying informed about the latest research and best practices in knee injury prevention and care will remain a cornerstone of effective patient care and education.

Reference

- Friel, N. A., & Chu, C. R. (2013). The role of ACL injury in the development of posttraumatic knee osteoarthritis. Clinical Sports Medicine, 32(1), 1-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.csm.2012.08.017

- Frobell, R. B., Roos, H. P., Roos, E. M., Ranstam, J., & Lohmander, L. S. (2010). Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five-year outcome of randomized trial. British Medical Journal, 340, c1472. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.c1472

- Muaidi, Q. I., Nicholson, L. L., Refshauge, K. M., & Herbert, R. D. (2009). Prognosis of conservatively managed anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 39(10), 769-790. DOI: 10.2165/11317830-000000000-00000

- Majewski, M., Susanne, H., & Klaus, S. (2006). Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: A 10-year study. The Knee, 13(3), 184-188. DOI: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005

- Griffin, L. Y., Albohm, M. J., Arendt, E. A., Bahr, R., Beynnon, B. D., DeMaio, M., … & Yu, B. (2006). Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a review of the Hunt Valley II meeting, January 2005. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(9), 1512-1532. DOI: 10.1177/0363546506286866

- Hewett, T. E., Myer, G. D., & Ford, K. R. (2005). Reducing knee and anterior cruciate ligament injuries among female athletes: a systematic review of neuromuscular training interventions. Journal of Athletic Training, 40(3), 287-295.

- Prodromos, C. C., Han, Y., Rogowski, J., Joyce, B., & Shi, K. (2007). A meta-analysis of the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears as a function of gender, sport, and a knee injury–reduction regimen. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 23(12), 1320-1325. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.003