Introduction

Coccydynia , or tailbone pain, is a condition characterized by severe pain located in the coccyx, often with radiation to the lower sacrum and perineum. This painful disorder can occur following direct trauma, such as a kick or fall, that directly impacts the coccyx. In addition, coccydynia can also occur after a difficult vaginal delivery, where the mechanical stress on this region is considerable.

The pain associated with coccydynia results mainly from tension on the sacrococcygeal ligament or, in some cases, from a fracture of the coccyx. This condition is more frequently observed in women than in men, which may be related to the anatomical peculiarities and hormonal changes associated with pregnancy and childbirth.

Coccydynia is often misunderstood and can significantly affect quality of life due to its persistent and painful nature. In this context, it is essential to explore the possible causes, associated symptoms, as well as the different treatment options available to relieve this pain and improve the comfort of those affected.

Anatomy

The coccyx is the region where the vertebral column terminates. Although the singular term “coccyx” suggests that it is a single bone, it is actually made up of 3 to 5 separate vertebral bodies, which vary considerably in their degree of fusion or nonfusion. It is also the site of insertion of the anterior and posterior sacrococcygeal ligaments, the anococcygeal ligaments, and the levator ani muscles. The coccyx articulates with the sacrum via a sacrococcygeal joint (consisting of a fibrocartilaginous intervertebral disc and bilateral zygapophyseal [facet] joints). The sacrococcygeal and intracoccygeal joints allow limited motion of the coccyx, which typically consists of forward flexion in a seated position.[1] Coccyx is a Greek word meaning cuckoo’s beak, because the side view of the coccyx resembles the side view of a cuckoo’s beak.

The outcome of direct vertical trauma to the coccyx can range from contusion to fracture-dislocation of the coccyx. Traumatic or non-traumatic injury to the coccygeal ligaments can result in dynamic instability of the coccyx (excessive movement of the coccyx while weight-bearing or sitting). Abnormal mobility of the coccyx can result in coccygeal pain. Abnormally mobile coccyxes can be either hypermobile (due to ligament laxity) or hypomobile (rigid). The coccyx can be subluxated anteriorly or posteriorly, unstable, or even dislocated[8].

The First Description of Coccydynia: A Historical Look

Coccydynia, or tailbone pain, is a condition that can be extremely debilitating, impacting the quality of life of those affected. The first known description of this condition dates back to 1588, by the Flemish physician Henri de Smet (1537-1614). In one particular case, De Smet observed and documented symptoms in his own wife after an accident.

In 1588 he wrote:

“My wife fell on her buttocks, and hurt her coccyx so much that she can no longer sit without pain, nor empty her bowels or bladder, nor cough, without great difficulty.”

This detailed description reveals the intense suffering and functional difficulties associated with coccydynia, including pain during daily activities such as sitting, defecating, urinating, or even coughing. De Smet highlights the significant impacts this condition can have on a person’s life, even at a time when treatments and medical understanding were much more limited.

Henri de Smet’s description marks a milestone in medical history, highlighting the importance of clinical observations in understanding musculoskeletal disorders. It also illustrates how physicians of the time, despite limited tools and knowledge, did their best to document and treat the conditions they encountered.

In 1726, a notable advance in the treatment of this condition was undertaken by the surgeon Jean-Louis Petit. Faced with the ineffectiveness of conservative methods to relieve coccyx pain, Petit decided to adopt a radical approach: amputation of the bony parts deemed responsible. This bold intervention aimed to eliminate the bony structures that caused the persistent pain, in the hope of permanently relieving patients.

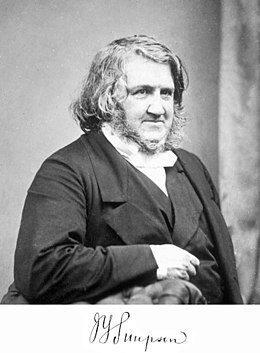

In 1859, the Scottish surgeon James Young Simpson (1811-1870) introduced a more precise term to designate this condition: coccyodynia . This term, derived from the Greek odynê (pain), was chosen to designate pain in the coccyx without prejudging its cause. According to Simpson, the advantage of this term was that it reflected an observable clinical fact, while leaving open the question of etiology. This nomenclature helped to unify medical terminology and facilitate communication about this condition across medical communities.

In 1950, the term “television disease” was used by an American author to describe coccydynia, highlighting prolonged poor sitting posture as a contributing factor. In the second half of the 20th century, understanding of the contributing factors of coccydynia evolved, including elements such as obesity and morphological variations of the coccyx. Discussions were divided between those who favored a psychopathological approach (such as anxiety neurosis or hysterical conversion pain) and those who considered a mechanical etiology, such as disc damage.

In 1994, the French physician Jean-Yves Maigne introduced an important advance in diagnosis: the notion of coccyx mobility disorders, which can be objectified by dynamic X-rays. This approach allows for a better understanding of the mechanics of the coccyx and refines treatment strategies for patients with coccygodynia.

Dr. Jean-Yves Maigne

The evolution of knowledge on coccydynia, from the first

Causes of Coccydynia: A Complete Overview

Coccydynia is a complex condition with widely varying causes, including mechanical, traumatic, and physiological factors. One of the most common causes of coccydynia is direct trauma to the coccyx. This type of injury can result from a kick, a fall on the buttocks, or excessive pressure placed on the coccygeal region. During such trauma, the coccyx, being a mobile bony structure located at the base of the spine, can fracture or displace, causing pain and inflammation. Women are particularly susceptible to these injuries due to prolonged sitting and body changes associated with pregnancy and childbirth. Difficult deliveries, particularly those requiring instrumental interventions or excessive pressure on the pelvic region, can also cause coccygeal pain due to stretching or trauma to the ligaments and surrounding tissues.

In addition to direct trauma, coccydynia can be caused by morphological abnormalities or pathological conditions. Variations in the structure of the coccyx, such as congenital deformities or acquired anatomical abnormalities, can contribute to instability or excessive mobility of this region, making the coccyx more susceptible to pain. Obesity is also a notable risk factor, as excess weight places increased pressure on the coccyx and adjacent tissues, increasing the risk of pain. Other causes include infections such as soft tissue abscesses or osteomyelitis, which can lead to inflammation and localized pain. Finally, conditions such as malignancies or pelvic floor disorders can also cause coccygeal pain, although these causes are less common. Thus, coccydynia often results from a complex interaction of various factors, requiring a thorough evaluation to determine the underlying cause and develop an appropriate treatment plan.

- Direct trauma: A fall, impact, or difficult delivery can cause injuries to the tailbone, leading to pain.

- Impaired coccyx mobility: Mobility disorders, such as ligament injuries, misalignments or subluxations of the coccyx, can cause pain.

- Obesity: Excess weight can put extra pressure on the tailbone, contributing to pain.

- Prolonged sitting: Poor posture or prolonged sitting, especially in front of a screen, can cause tension in the coccyx.

- Infections: Local infections or inflammations, although less common, can cause coccygeal pain.

- Tumors: Tumors in the tailbone can cause pain, although this is rare.

- Muscle problems: Muscle tension or spasms in the muscles surrounding the tailbone can cause pain.

- Joint problems: Conditions such as arthritis can affect the tailbone joints.

- Childbirth: Women may develop tailbone pain after childbirth due to the pressure exerted during labor.

- Cauda equina syndrome: Compression of the nerves in the tailbone, also called cauda equina syndrome, can cause pain, although this is rare.

Coccydynia Symptoms: Identifying and Understanding the Pain

Coccydynia presents primarily with pain localized to the coccyx, but symptoms may also radiate to adjacent areas such as the sacrum and perineum. This pain is often described as sharp, throbbing, or dull, and may vary in intensity with body movements and positions. Patients with coccydynia typically report pain that is worse when sitting, especially when sitting on hard or uncomfortable surfaces. Relief may be temporary when standing or changing position, but pain may return when sitting again. Pain may also occur with prolonged periods of standing or movements such as bending forward or standing up suddenly. This pain is often associated with increased sensitivity to touch in the coccygeal region, making even everyday activities such as sitting down or standing up particularly difficult.

In addition to localized pain, coccydynia can cause secondary symptoms that affect surrounding body functions. Women, in particular, may experience worsening symptoms during the premenstrual period due to hormonal fluctuations that can exacerbate pelvic pain. Pain may also be present during defecation or urination, due to the involvement of the pelvic floor muscles and tissues in the coccygeal region. These symptoms may be accompanied by muscle spasms in the levator ani muscles, which make up the deep pelvic floor. In some cases, patients may also experience radiating pain to the buttocks or thighs, often due to the spread of pain along surrounding nerves. These secondary manifestations can complicate the diagnosis and treatment of coccydynia, requiring a multifaceted approach to effectively relieve symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life.

- Localized coccyx pain: Pain often described as a feeling of pressure, tenderness, or sharp pain directly over the coccyx.

- Pain when sitting: The pain usually gets worse when the person sits, especially on hard surfaces.

- Pain when changing positions: Transitioning between sitting and standing, or vice versa, may cause a temporary increase in pain.

- Pain on prolonged standing: Pain may also intensify after prolonged periods of standing.

- Pain while walking: Some individuals may experience worsening pain while walking, especially on uneven surfaces.

- Pain during labor: Women may develop tailbone pain during or after childbirth.

- Pain during sexual activity: Pain may be worse during or after intercourse.

- Tingling or Numbness: Some patients may experience a tingling or numbness sensation around the tailbone.

- Increased sensitivity to touch: The area around the tailbone may be particularly sensitive to touch.

- Pain radiating down the legs: In some cases, pain may radiate down the spine or along the lower limbs.

- Coccyx stiffness: A feeling of stiffness or limited movement in the tailbone.

- Discomfort during defecation: Pressure during defecation can cause or worsen tailbone pain.

- Pain when changing position in bed: Lying down or getting out of bed can cause a temporary increase in pain.

- Chronic pain: Coccydynia can progress to a chronic condition with pain that persists over a prolonged period of time.

- Pain-related fatigue: People with coccydynia may experience physical and mental fatigue due to the constant pain.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of coccydynia, or coccygeal pain, can vary depending on the underlying cause. However, here are some general mechanisms that may contribute to coccyx pain:

- Trauma: Direct trauma, such as a fall on the buttocks, can cause injuries to the structures of the coccyx, including fractures, dislocations, or ligament injuries.

- Impaired mobility: Mobility disorders, such as ligament injuries or spinal misalignments, can cause instability or stiffness in the tailbone, contributing to pain.

- Nerve compression: Compression of nerves in the tailbone area, such as the pudendal nerve, can cause painful, tingling, or numb sensations.

- Inflammation: Inflammation of the tissues around the tailbone, whether due to trauma, infections, or other causes, can cause pain.

- Joint problems: The joints between the coccyx and sacrum can be prone to inflammatory or degenerative problems, causing pain.

- Local hypersensitivity: Changes in local sensitivity around the coccyx may contribute to the perception of pain.

- Psychological implications: Although coccygeal pain often has physical causes, psychological factors such as stress or anxiety can contribute to its intensity and persistence.

- Increased pressure: Excess weight, obesity, or prolonged pressure on the tailbone area (e.g., prolonged sitting) can increase pressure on the structures, contributing to pain.

- Abnormal development of the coccyx: Congenital or acquired morphological variations of the coccyx can lead to problems with positioning or mobility.

Differential Diagnosis of Coccydynia: Approach and Considerations

The differential diagnosis of coccydynia is essential to rule out other pathologies that may present similar symptoms. In fact, several medical conditions can mimic or overlap with coccygeal pain, complicating the precise diagnosis. Among the main conditions to consider, pain or inflammation of the sacroiliac joint is notable. This joint, located between the sacrum and the pelvis, can also cause localized pain in the pelvic region and buttocks, often exacerbated by specific movements or prolonged sitting. Sciatica, resulting from irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve, can also present radiating pain that can be confused with that of coccydynia, although sciatica usually manifests itself with pain that radiates down the leg. Other pathologies such as hemorrhoids, which can also cause pain in the rectal and pelvic region, should be considered, especially in cases of acute pain during defecation.

The differential diagnosis should also include evaluation of muscle pain and pelvic floor disorders. Pelvic floor muscle pain, often caused by spasms or excessive muscle tension, can mimic coccygeal pain and cause similar discomfort in the coccyx. Malignant tumors, such as chordoma or chondrosarcoma, are rare but serious causes of coccygeal pain, requiring a thorough evaluation to rule out these serious conditions. Finally, less common but possible conditions include infections such as osteomyelitis or soft tissue abscesses, which can cause localized pain and inflammation in the coccygeal region. For an accurate diagnosis, a comprehensive clinical approach including a detailed medical history, a thorough physical examination, and additional investigations such as X-rays, MRI, or ultrasound is crucial to distinguish coccydynia from other conditions and determine the best treatment approach.

- Coccyx Fracture: A coccyx fracture can cause symptoms similar to coccydynia, but requires an X-ray evaluation to confirm.

- Hemorrhoids: Hemorrhoids can cause pain in the anal area, sometimes confused with tailbone pain.

- Pelvic infections: Infections in the pelvic area can cause pain that radiates to the tailbone.

- Tumors: Tumors in the pelvic area can cause pain that may be confused with coccydynia.

- Joint or lower back problems: Disorders of the sacroiliac joints or lumbar discs can manifest with similar symptoms.

- Gynecologic problems: Certain gynecologic conditions, such as endometriosis, can cause pelvic and coccygeal pain.

- Pudendal nerve disorders: Pudendal nerve problems can cause pain in the pelvic area and sometimes be confused with coccydynia.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): IBS can cause abdominal pain that may be felt in the tailbone area.

- Sacroiliac Arthritis: Inflammation of the sacroiliac joints can cause pain in the tailbone area.

- Narrow anal canal syndrome: This condition can cause rectal and coccygeal pain.

Recommendations for the Management of Coccydynia: Approaches and Interventions

Management of coccydynia requires a multimodal approach to relieve pain, improve patient comfort, and address the underlying causes of the condition. Among the first recommendations, the use of appropriate cushions is crucial. U-shaped cushions or circular cushions, sometimes called “donut cushions,” are designed to reduce pressure on the coccyx when the patient is sitting. These cushions help distribute body weight more evenly, providing significant relief for those with coccygeal pain. In addition, adjustments to sitting habits can also help alleviate symptoms. Sitting upright and varying positions are recommended to avoid prolonged pressure on the coccyx. Cold or hot compresses can be applied topically to reduce inflammation and soothe pain, although it is important to use them with caution to avoid skin breakdown.

In parallel, more specific interventions may be considered to treat coccydynia. Weight loss may be beneficial, especially in cases where obesity contributes to increased pressure on the coccygeal region. Manual treatments, such as osteopathic manipulation techniques, may also offer relief by targeting tension and dysfunction in the coccyx and surrounding tissues. Massage of the pelvic floor muscles and adjacent tissues may help reduce muscle spasms and improve coccyx mobility. If pain persists despite these interventions, more invasive options may be considered, such as corticosteroid injections to reduce inflammation or, in extreme cases, surgery to remove or stabilize the coccyx. Regular assessment by a healthcare professional is essential to tailor treatments to the individual needs of the patient and ensure effective management of coccydynia.

Here are some general recommendations that may help relieve the symptoms of coccydynia:

- Using a donut cushion: When sitting, use a donut cushion or orthopedic cushion to reduce pressure on the tailbone. This can help relieve discomfort during prolonged periods of sitting.

- Avoid prolonged sitting: Try to limit the amount of time you spend sitting, especially on hard surfaces. If you must sit for long periods, take frequent breaks to stand, stretch, and change positions.

- Applying ice or heat: Applying ice can help reduce inflammation and relieve pain. Use an ice pack wrapped in a thin cloth to prevent burns. Some individuals may also prefer heat in the form of a heating pad.

- Muscle strengthening exercises: Specific exercises can help strengthen the pelvic floor muscles, which can help support the tailbone. Consult a healthcare professional, such as a physical therapist, for specific exercise recommendations.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Over-the-counter medications such as ibuprofen can help reduce the pain and inflammation associated with coccydynia. However, check with your doctor before taking any medications, especially if you have underlying health conditions.

- Osteopathy or physiotherapy: Health professionals such as osteopaths or physiotherapists can use manual techniques to help release muscle tension and restore mobility in the coccygeal region.

- Avoid trauma: Avoid sitting abruptly and be aware of your posture. Also avoid activities that could put excessive pressure on the tailbone.

- Warm Baths: Taking warm baths can help relax muscles and relieve pain. Optionally, add Epsom salt to the water for a relaxing effect.

- Change your position: If you work at a desk, try to stand up and stretch regularly. Use ergonomic chairs to support your back.

- Medical consultation: If pain persists or worsens, see a doctor for a thorough examination and to discuss more specific treatment options, including corticosteroid injections or other medical interventions.

Osteopathy and cossidynia

Here is how osteopathy could be applied in the context of coccydynia:

- Assessment: The osteopath will begin with a thorough assessment to understand the nature of the coccydynia, examining posture, spinal mobility, surrounding muscles, and assessing the coccygeal region itself.

- Reducing muscle tension: Muscle tension around the tailbone can contribute to pain. The osteopath can use manual techniques to release this tension, thus promoting muscle relaxation.

- Restoring mobility: If movement restrictions are identified in the coccyx or surrounding joints, the osteopath can use gentle manipulations to improve mobility and reduce pain.

- Postural adjustments: Posture advice and postural adjustments can be provided to avoid excessive pressure on the coccyx, which may be particularly important for people who sit for prolonged periods.

- Exercises and stretches: Specific exercises and stretches may be recommended to strengthen the pelvic stabilizing muscles and promote better stability.

Manual processing

Early descriptions of manual treatments for coccydynia primarily emphasize coccyx repositioning, without specifically addressing repeated treatments. However, the first mention of repeated manual treatment in the form of massage is from Berghman’s work in 1873. Berghman reported the case of a 30-year-old woman who had suffered from coccydynia for two years and experienced acute pain when rising from a sitting position. This patient experienced significant relief of her pain after eight days of massage treatment, and she subsequently made a full recovery.

Another notable contributor to the evolution of manual treatments for coccydynia was Duncan, who for the first time provided statistics on the success rate of these approaches. His study of 54 patients with coccydynia revealed that most experienced relief within a month of starting nonoperative treatment. However, some required up to six months of treatment to achieve positive results. These early statistical data laid the foundation for evaluating the effectiveness of manual treatments for coccydynia.

Evolution of Manual Treatment of Coccydynia: From Reduction to Repetitive Massage

Manual treatment of coccydynia, a painful condition affecting the coccyx, has evolved significantly over the centuries. Initially, approaches focused on repositioning the coccyx, without repeat treatment, which often limited their long-term effectiveness. Early manual methods of treating coccydynia involved attempts at coccyx readjustment, usually performed only once. These approaches, while important in the early development of treatments, did not allow for ongoing pain management, which could lead to recurrences or persistent pain.

In 1873, Berghman marked a turning point in the treatment of coccydynia by introducing the use of repetitive massage as an effective method to relieve this condition. He reported the case of a 30-year-old woman who had suffered from acute pain related to coccydynia for two years. Berghman used massage as the primary treatment for eight days, and the patient experienced significant relief from her pain. This was a pivotal observation, demonstrating that repetitive massage could have a lasting positive impact on coccydynia. Berghman’s method paved the way for more sophisticated manual approaches and set an important precedent for the use of massage in the treatment of this painful condition.

Berghman’s advances encouraged other practitioners to explore and refine massage techniques for coccydynia. The introduction of repeated treatments allowed for more effective management of symptoms, focusing not only on immediate relief but also on preventing the pain from recurring. This approach highlighted the importance of ongoing manual interventions and contributed to the evolution of treatment protocols for coccydynia.

Over time, other practitioners, such as George Thiele, refined these techniques by focusing on massage of the levator ani and coccyx muscles. Thiele, who treated more than 300 patients during his career, recommended gentle, repetitive massage to relax spastic muscles and improve coccyx function. His methods reinforced the idea that manual treatments could offer a noninvasive and effective solution to manage coccygeal pain, solidifying the role of massage in the management of coccydynia.

In conclusion, the evolution of manual treatments for coccydynia illustrates the importance of continued advances in the management of chronic pain. Berghman’s introduction of repetitive massage marked a significant turning point, paving the way for more refined therapeutic approaches and a better understanding of the mechanisms of coccygeal pain relief. These developments have enriched the available treatment options, providing patients with more effective solutions to manage this painful condition and improve their quality of life.

George Thiele: Pioneer of Manual Treatments for Coccydynia

George Thiele, a renowned Kansas City-based practitioner, has left an indelible mark on the field of coccydynia treatment. Throughout his career, Thiele has dedicated himself to the in-depth study of this complex condition, successfully treating over 300 patients. His contributions are distinguished by the innovative integration of manual methods in the treatment of coccygeal pain, and he has shared his extensive knowledge through a series of published articles over a 27-year period. The impact of his work extends far beyond clinical practice; he has played a key role in the validation and acceptance of manual treatments for coccydynia, enriching the field of pelvic pain management.

Thiele formulated a novel hypothesis that a large proportion of coccydynia cases could be attributed to spasms of the levator ani and coccyx muscles. This approach marked a turning point in the understanding and treatment of coccydynia. According to Thiele, pain relief could be effectively achieved by gentle, repetitive massage of the affected muscles. He recommended daily massage sessions for several days, with a gradual decrease in frequency as the pain subsided. This method aimed to relax the spastic muscles and improve coccygeal function, thus offering a noninvasive alternative to more radical treatments.

Thiele’s work not only shed valuable light on the underlying causes of coccydynia but also established widely adopted manual treatment protocols. His method demonstrated that simple but effective techniques could relieve pain and improve the quality of life of patients with coccydynia. The positive results obtained in his patients were crucial in legitimizing these practices, highlighting the effectiveness of manual massage as a non-invasive treatment.

Prior to Thiele’s contributions, coccyx manipulation under anesthesia had been described in 1937 by Hobart, who used delicate manipulation techniques to readjust the coccyx, often successfully. This period also marked the first descriptions of manual treatments for coccydynia, with experimental approaches and early clinical observations that set the stage for Thiele’s work.

Beyond his clinical contributions, Thiele has also played an important role in research and dissemination of knowledge on coccydynia. His publications have offered new and practical perspectives, facilitating the understanding of the mechanisms of coccygeal pain and treatment strategies. His work has helped to refine therapeutic approaches and paved the way for better recognition of manual treatments in the management of this painful condition.

In conclusion, George Thiele’s work has been instrumental in the development and validation of manual treatments for coccydynia. His innovative method of massaging the levator ani and coccyx muscles marked a significant advancement in the management of coccygeal pain, enriching the field of manual therapy. Thanks to his contributions, coccydynia is now better understood and treated, offering patients more effective and less invasive treatment options.

In summary, George Thiele has played a pivotal role in the history of coccydynia management. His dedication to the in-depth study of this condition and his efforts to share his findings have had a lasting impact, leaving a legacy in the field of manual treatments for coccygeal pain.

Cushion to relieve coccydynia

Using a foam cushion while sitting for coccydynia may provide symptomatic relief and allow the sacrococcygeal ligament to heal.

Using a foam cushion while sitting for coccydynia is a simple but often effective approach to relieving the painful symptoms associated with this condition. The coccyx, or tail bone, can become inflamed or injured, resulting in persistent pain, especially when sitting.

The foam cushion, designed specifically to provide support to the coccyx, helps reduce pressure on this delicate area. By providing additional support, the cushion helps redistribute body weight in a balanced manner, relieving tension on the sacrococcygeal ligament.

The sacrococcygeal ligament is a fibrous structure that connects the sacrum to the end of the coccyx. When subjected to excessive stress or repeated movements, it can become inflamed, causing a painful sensation, especially during activities that place stress on the coccygeal region, such as sitting.

Using the foam cushion while sitting creates a cushioned surface that reduces direct pressure on the tailbone, facilitating the healing process of the sacrococcygeal ligament. By minimizing contact between the tailbone and the seating surface, the cushion helps prevent worsening of symptoms and promotes faster recovery.

It is important to note that while using the cushion may provide symptomatic relief, it is not necessarily a cure. People with coccydynia may also benefit from medical consultations to identify the underlying cause of the pain and develop a comprehensive treatment plan.

In summary, using a foam cushion while sitting represents a practical, non-invasive approach to relieving the pain associated with coccydynia. This device provides targeted support to the coccyx, allowing the sacrococcygeal ligament to heal while facilitating comfort during seated activities.

Using a Donut Cushion

Using a donut cushion is a common practice to relieve the symptoms of coccydynia. This type of cushion, also called a ring cushion or orthopedic donut cushion, is specifically designed to provide relief from tailbone pain.

The donut cushion features a hole in the center, creating an opening at the tailbone. This design helps reduce pressure on this delicate area when sitting. By sitting directly on the central opening of the cushion, the tailbone does not come into direct contact with the seat surface, minimizing friction and pressure.

The main benefit of using a donut cushion is its ability to relieve coccygeal pain by providing ergonomic support. It helps distribute body weight evenly, preventing excessive pressure from being concentrated on the coccyx. This balanced distribution helps prevent symptoms from worsening and can promote greater comfort during prolonged periods of sitting.

People suffering from coccydynia, whether due to injury, inflammation, or other causes, may find temporary relief by using this type of cushion. It is important to note that while the donut cushion may alleviate symptoms, it does not address the underlying cause of tailbone pain. Medical consultations are recommended to thoroughly evaluate the condition and develop an appropriate treatment plan.

In summary, the use of a donut cushion represents a practical solution to relieve coccygeal pain by providing suitable support during sitting. This ergonomic cushion can be an effective complement to comprehensive therapeutic approaches aimed at treating coccydynia.

Good posture to avoid pressure on the coccyx

Maintaining good posture is essential to prevent excess pressure on the tailbone and can help relieve symptoms of coccydynia. Here are some tips for maintaining good posture and reducing pressure on the tailbone: When sitting, make sure to sit with your back straight, shoulders relaxed, and feet flat on the floor. Use a donut cushion or orthopedic cushion if necessary to reduce pressure on the tailbone. Try to distribute your weight evenly across both buttocks rather than leaning to one side. This can prevent excess pressure on the tailbone.

Suggested book

A book that might be useful to you to deepen your knowledge about coccydynia is:

Title: “Tailbone Pain Relief Now!”

Author: Patrick M. Foye, MD

This book, written by Dr. Patrick Foye, is a valuable resource for those suffering from coccyx pain. Dr. Foye is a renowned expert in the field of coccygeal pain and his book offers practical advice, information on the anatomy of the coccyx, treatment options, and patient stories. It is designed to help people with coccydynia understand their condition and explore pain relief strategies. Before undertaking any treatment, it is always recommended to consult a healthcare professional for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a thorough study of the history of coccydynia management reveals a significant evolution of therapeutic approaches over the decades. Practitioners such as George Thiele and Hobart have played crucial roles in introducing innovative methods, ranging from manual massage to manipulation under anesthesia. Their contributions have enriched our understanding of coccygeal pain and paved the way for diversified treatment options.

The 1930s and 1940s were a period of bold exploration, when different approaches were tested to alleviate coccygeal pain. The advances of this era laid the foundation for future research and helped expand the range of treatment options available today.

The use of foam or donut cushions, as well as the promotion of good posture, remain simple but effective strategies to relieve the symptoms of coccydynia. These non-invasive approaches can provide symptomatic relief and contribute to the healing process of the sacrococcygeal ligament.

Finally, suggested reading, particularly the book “Tailbone Pain Relief Now!” by Dr. Patrick Foye, can provide additional information for those seeking to better understand and manage tailbone pain.

It is essential to emphasize that each case of coccydynia is unique, and consultation with a health professional for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate advice remains imperative. The history of coccydynia management illustrates the perseverance of health professionals in the search for effective solutions to relieve pain and improve the quality of life of people affected by this condition.

Reference:

- Focus PM. Coccydynia: Tailbone Pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017 Aug;28(3):539-549. [ PubMed ]2.

- Focus PM. Stigma against patients with coccyx pain. Pain Med. 2010 Dec;11(12):1872. [ PubMed ]3.

- Sugar O. Coccyx. The bone named for a bird. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Feb 01;20(3):379-83. [ PubMed ]4.

- Woon JT, Stringer MD. Clinical anatomy of the coccyx: A systematic review. Clin Anat. 2012 Mar;25(2):158-67. [ PubMed ]5.

- Lirette LS, Chaiban G, Tolba R, Eissa H. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner J. 2014 Spring;14(1):84-7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]6.

- Kerr EE, Benson D, Schrot RJ. Coccygectomy for chronic refractory coccygodynia: clinical case series and literature review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011 May;14(5):654-63. [ PubMed ]7.

- Patijn J, Janssen M, Hayek S, Mekhail N, Van Zundert J, van Kleef M. 14. Coccygodynia. Pain Pract. 2010 Nov-Dec;10(6):554-9. [ PubMed ]8.

- Kim NH, Suk KS. Clinical and radiological differences between traumatic and idiopathic coccygodynia. Yonsei Med J. 1999 Jun;40(3):215-20. [ PubMed ]9.

- Postacchini F, Massobrio M. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983 Oct;65(8):1116-24. [ PubMed ]10.

- Doursounian L, Maigne JY, Jacquot F. Coccygectomy for coccygeal spicule: a study of 33 cases. Eur Spine J. 2015 May;24(5):1102-8. [ PubMed ]11.

- Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Dec 01;25(23):3072-9. [ PubMed ]12.

- Nathan ST, Fisher BE, Roberts CS. Coccydynia: a review of pathoanatomy, aetiology, treatment and outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Dec;92(12):1622-7. [ PubMed ]13.

- Fortin JD, Falco FJ. The Fortin finger test: an indicator of sacroiliac pain. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1997 Jul;26(7):477-80. [ PubMed ]14.

- Maigne JY, Guedj S, Straus C. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Lateral roentgenograms in the sitting position and coccygeal discography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994 Apr 15;19(8):930-4. [ PubMed ]15.

- Maigne JY, Pigeau I, Roger B. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the painful adult coccyx. Eur Spine J. 2012 Oct;21(10):2097-104. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]16.

- Maigne JY, Chatellier G. Comparison of three manual coccydynia treatments: a pilot study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Oct 15;26(20):E479-83; discussion E484. [ PubMed ]17.

- Maigne JY, Tamalet B. Standardized radiologic protocol for the study of common coccydynia and characteristics of the lesions observed in the sitting position. Clinical elements differentiating dislocation, hypermobility, and normal mobility. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996 Nov 15;21(22):2588-93. [ PubMed ]