Primary bone cancers

Primary bone cancers are conditions in which malignant cells initially form in the bones themselves, thus distinguishing these cancers from metastatic cancers that spread to the bones from other parts of the body. These tumors can be classified into several types, but among the most common are osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and multiple myeloma. Each type has distinct characteristics in terms of location, age of prevalence, and biological behavior.

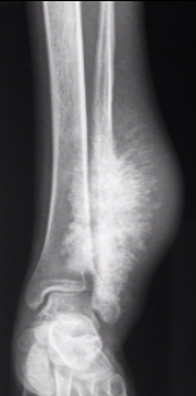

Osteosarcoma is one of the most common primary bone cancers, usually developing in long bones such as the arms and legs. It often affects adolescents and young adults. Characterized by the production of osteoid, a bone substance, osteosarcoma can be diagnosed through imaging techniques such as X-rays and often requires a combination of surgery and chemotherapy for treatment.

Chondrosarcoma is a malignant tumor that forms in the cartilage of bones. Unlike osteosarcoma, it usually occurs in older adults. Chondrosarcomas can affect various bones, including the pelvis and arms, and are diagnosed using advanced imaging techniques such as MRI. Surgery often remains the primary treatment modality for this form of bone cancer.

Ewing sarcoma, on the other hand, is a malignant bone tumor that primarily affects adolescents, particularly in the second decade of life. Classified as a highly metastatic sarcoma, Ewing sarcoma can spread rapidly. Diagnosis usually involves a combination of imaging techniques and biopsies. Historically, the prognosis was poor, but with advances in treatments such as surgery, radiation therapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy, the five-year survival rate has improved.

Multiple myeloma, although it primarily affects the bone marrow, is also classified as a primary bone cancer. It is a disease characterized by the malignant proliferation of plasma cells, a type of immune cell, in the bone marrow. Multiple myeloma can cause bone damage, fractures, and pain. Treatment options include chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation, and other targeted therapies.

Diagnosis of primary bone cancers relies on imaging methods such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, MRIs, and bone scans. Biopsies are often necessary to confirm the malignant nature of the tumor and guide the treatment plan. Treatment may involve surgery to remove the tumor, chemotherapy to eliminate remaining cancer cells, and radiation therapy to specifically target the affected area.

The prognosis for primary bone cancer depends on a variety of factors, including the type of cancer, stage at diagnosis, tumor location, and response to treatment. Although these cancers can be aggressive, continued advances in medical research and treatment have improved survival prospects over the years. A multidisciplinary approach involving oncologists, orthopedic surgeons, radiologists, and other healthcare professionals is often necessary to provide patients with the best possible care.

The four most common types of primary bone cancer are:

- Multiple myeloma:

- Multiple myeloma is the most common primary bone cancer.

- It is a malignant tumor of the bone marrow, the soft tissue in the center of many bones that is responsible for producing blood cells.

- Treatment for multiple myeloma often involves a combination of chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and, in some cases, stem cell transplantation.

- Osteosarcoma:

- Osteosarcoma is the second most common primary bone cancer.

- It is a mesenchymal neoplasm that produces osteoid as well as woven bone matrix.

- The diagnosis of osteosarcoma is based on the presence of osteoid matrix, which can vary in quantity and structure.

- Ewing’s sarcoma:

- Ewing sarcoma is the second most common primary malignant bone tumor.

- It mainly affects adolescents in the second decade of life and is classified as a highly metastatic sarcomas.

- Despite its aggressiveness, the 5-year survival rate has increased significantly thanks to advances in treatment, including radiation therapy, surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Chondrosarcoma:

- Chondrosarcoma is a malignant tumor composed of cartilage-producing cells.

- Unlike the other types mentioned, chondrosarcoma develops from cartilage, not the bone itself.

- Treatment usually involves surgery to remove the tumor, and radiation therapy may also be used in some cases.

Benign bone tumors

A benign tumor is a mass of abnormal cells that grows in a specific tissue of the body without invading nearby tissues or spreading to other parts of the body. Unlike malignant tumors, benign tumors are generally not considered cancerous, and they tend to grow slowly and in a localized manner. Although their presence can cause symptoms or complications, they are often less of a concern than malignant tumors.

The fundamental characteristic of a benign tumor is its confinement to a specific area, without invasive or metastatic capacity. These tumors are usually well encapsulated, surrounded by a membrane that limits their expansion and interaction with surrounding tissues. This encapsulation is often a key aspect that distinguishes benign tumors from malignant tumors, which tend to infiltrate neighboring tissues aggressively.

An important thing to understand is that while benign tumors are not considered cancers, they can still cause problems. Their impact on health depends on several factors, including their size, location, and the pressure they put on surrounding tissues. Some benign tumors may remain asymptomatic and are only detected incidentally during routine medical exams, while others may cause symptoms such as pain, swelling, or impaired organ function.

One of the characteristics of benign tumors is their relatively slow growth compared to malignant tumors. This gradual growth can allow healthcare professionals to carefully monitor the tumor over time and decide on the appropriate treatment based on how the situation evolves. In many cases, a surveillance approach is taken, meaning that the tumor is regularly monitored with medical examinations and imaging tests, and treatment is only considered if the tumor shows signs of growth or develops symptoms.

Diagnosis of benign tumors often relies on imaging techniques such as X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs, which allow doctors to visualize the size, shape, and location of the tumor. In some cases, a biopsy may be performed to confirm the benign nature of the tumor by examining tissue samples under a microscope.

Treatment for benign tumors depends on several factors, including the size of the tumor, its location, and the symptoms it causes. In many cases, especially if the tumor is small and does not cause symptoms, no immediate intervention is necessary. However, if the tumor is likely to cause problems or poses health risks, treatment options such as surgery to remove the tumor may be considered.

In summary, a benign tumor is a mass of abnormal cells that develops locally in a specific tissue without the aggressive characteristics of malignant tumors. Although they are usually not cancerous, benign tumors may require monitoring and, in some cases, appropriate treatment to avoid any negative impact on health. Early diagnosis, careful monitoring and close communication between the patient and the medical team are essential for optimal management of benign tumors.

Here is a list of some of the most common benign bone tumors:

- Osteoid osteoma:

- A small tumor often located in the long bones, which can cause pain.

- Osteoblastoma:

- A benign tumor that also forms in long bones, usually associated with pain.

- Chondroma:

- A benign tumor made of cartilage that can form in bones.

- Non-ossifying fibroma (or fibrous dysplasia):

- A benign lesion that can affect the bones, often seen in young people.

- Enchondroma:

- A benign tumor composed of cartilage that usually forms in the small joints of the hands and feet.

- Bone geode:

- A fluid-filled cavity that can form in bones, often without symptoms.

- Bone hemangioma:

- A benign tumor formed from abnormal blood vessels in the bones.

- Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB):

- A benign lesion that can cause local bone degradation, often seen in young adults.

- Eosinophilic granuloma:

- A benign lesion associated with eosinophilic cells, often seen in the bones of the hands and feet.

- Cortical osteoma:

- A benign tumor that develops from the outer layer of bones.

Classification of a bone tumor, according to the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) proposes a classification of tumors according to their origin, based on the type of tissue or cell from which the tumor develops. Here is a brief description of some types of tumors according to their origin:

- Bone Tumors:

- Osteosarcoma: It is a malignant tumor that develops from bone cells. It is often seen in adolescents and young adults.

- Osteoid osteoma: A benign bone tumor that can cause pain, usually treated by surgical removal.

- Cartilage Tumors:

- Chondrosarcoma: A malignant tumor that forms from cartilage cells. It can develop in bones and is more common in adults.

- Enchondroma: A benign tumor of cartilage that can develop inside bones.

- Giant Cell Tumors:

- Giant cell tumor of bone: This usually involves the ends of long bones and may be benign or, more rarely, malignant.

- Medullary Tumors:

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma: A thyroid cancer that develops from cells in the thyroid medulla.

- Vascular Tumors:

- Hemangioma: A benign tumor formed of blood vessels. They can occur in any bone.

- Other Tumors:

- Granular cell tumor: An often benign tumor that can develop in various tissues, including bone.

- Clear cell tumor: It can occur in various organs, including bones, and can be benign or malignant depending on the location.

Each type of tumor has its specific clinical, histological and prognostic characteristics. Treatment varies depending on the nature of the tumor, ranging from surgical removal to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, depending on the type and stage of the disease. Obtaining an accurate diagnosis is essential to determine the optimal treatment plan.

Causes of bone tumors

Bone tumors can have a variety of causes, and it is important to note that most of them are not directly related to specific behaviors or lifestyle choices. The causes of bone tumors can be classified into two main categories: benign tumors and malignant tumors.

Causes of benign bone tumors

- Genetic factors: Some types of benign tumors, such as fibrous dysplasia or osteochondroma, may be linked to inherited genetic mutations.

- Environmental factors: Environmental exposures to certain chemicals or radiation can sometimes be associated with the development of benign bone tumors.

- Hormonal factors: Certain hormonal changes can influence the growth of benign tumors. For example, chondromas can be influenced by hormonal changes during growth.

Causes of malignant bone tumors

- Genetic mutations: Primary bone cancers, such as osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma, may be associated with genetic mutations acquired over time. These mutations can affect the normal control of cell growth.

- Hereditary factors: Some people may be predisposed to developing bone cancers due to family genetic predispositions. However, the majority of bone cancers are not directly inherited.

- Ionizing radiation: Prolonged exposure to ionizing radiation, whether for medical or occupational purposes, may increase the risk of developing bone cancer.

- Repeated bone trauma: Some types of bone tumors, particularly osteosarcomas, have been linked to repeated bone trauma, although the exact relationship is not always clear.

- Inherited genetic diseases: Certain genetic diseases, such as Paget’s disease, can increase the risk of developing bone tumors.

- Pre-existing conditions: Certain genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis, are associated with an increased risk of developing bone tumors.

Pathophysiology of bone tumor

The pathophysiology of bone tumors involves complex processes that govern the development, growth, and interaction of tumor cells with surrounding bone tissue. It is important to understand that bone tumors can be benign or malignant, and each type can have specific pathophysiological characteristics. Here is a general overview of the pathophysiology of bone tumors:

Formation of Benign Tumors

- Cellular origin: Benign tumors can develop from various types of cells present in bone tissue, such as bone cells, cartilage cells, or other mesenchymal cells.

- Abnormal cell division: Benign tumors often result from abnormal cell division, where cells proliferate uncontrollably but lack the ability to infiltrate locally or spread to other parts of the body (metastasize).

- Tissue compression: As the tumor grows, it may put pressure on surrounding tissues, causing local symptoms such as pain or deformity.

Formation of Malignant Tumors

- Cellular transformation: Malignant tumors, or cancers, result from cellular transformation where normal cells acquire genetic mutations leading to uncontrolled growth, loss of apoptosis (programmed cell death), and the ability to invade.

- Local invasion: Malignant tumor cells can invade surrounding tissues, destroy normal bone structure, and cause lytic lesions.

- Formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis): Malignant tumors have the ability to stimulate the formation of new blood vessels to ensure a continuous supply of nutrients and oxygen, thereby promoting their growth.

- Metastasis: Malignant tumor cells can break away from the primary tumor, travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, and establish new tumors at a distance, often in other parts of the body.

Contributing Factors

- Genetics: Genetic mutations may play a role in the development of bone tumors, whether at the level of tumor suppressor genes, oncogenes or other cellular regulators.

- Environmental Factors: Exposure to certain carcinogens, repeated trauma, or other environmental factors may contribute to the development of bone tumors.

- Hormones: Some types of bone tumors can be influenced by hormonal imbalances.

Symptoms of bone tumors

Symptoms of bone tumors can vary depending on the type of tumor (benign or malignant), its location in the body, its size, and its stage of development. It is important to note that many bone tumors may be asymptomatic in their early stages and may be discovered incidentally during routine medical exams or medical imaging. However, when symptoms do occur, they may include:

General symptoms of bone tumors

- Pain: Pain is one of the most common symptoms. It can be persistent, deep, and increase over time. Pain may be felt directly at the site of the tumor or radiate to other parts of the body.

- Swelling or swelling: A bone tumor may cause swelling or swelling at the affected site. This may be visible or palpable.

- Stiffness or limitation of movement: The presence of a bone tumor can cause joint stiffness or limitation of movement in the affected area.

- Spontaneous fractures: Bone tumors sometimes weaken bones, increasing the risk of spontaneous fractures, which are fractures without obvious trauma.

Specific symptoms depending on the type of tumor

- Osteosarcoma:

- Severe, persistent pain, often at night.

- Swelling or mass at the affected site.

- Limitation of mobility.

- Chondrosarcoma:

- Pain that may be intermittent.

- Swelling or swelling.

- Pathological fractures.

- Ewing’s sarcoma:

- Pain, swelling, and tenderness at the tumor site.

- Unexplained fever.

- Fatigue and weight loss.

- Multiple myeloma:

- Bone pain, often in the back or ribs.

- Spontaneous fractures.

- Anemia, fatigue, and increased risk of infections.

General symptoms of benign bone tumors

- Asymptomatic: Many benign bone tumors may be asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during routine medical examinations or medical imaging.

- Mild local pain: Some benign tumors can cause mild local pain that may be intermittent.

- Mild swelling: Mild swelling or swelling may sometimes be seen at the tumor site.

Specific symptoms depending on the type of benign tumor

- Osteoid osteoma:

- Localized pain, often intense, which can be relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Osteoblastoma:

- Pain that may be intense, but generally less severe than that of osteoid osteoma.

- May cause swelling and tenderness.

- Chondroma:

- Often asymptomatic, but may cause pain if the tumor compresses nerves or surrounding tissues.

- May cause slight swelling.

- Non-ossifying fibroma (or fibrous dysplasia):

- May be asymptomatic.

- Bone pain and possible pathological fractures.

- Enchondroma:

- Often asymptomatic.

- May cause pain if the tumor causes fractures.

- Bone geode:

- Usually asymptomatic.

- May cause pathological fractures.

- Bone hemangioma:

- Often asymptomatic.

- May cause pain or weakness if the tumor bleeds into surrounding tissues.

- Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB):

- May cause pain and swelling.

- May cause bone deformity.

- Eosinophilic granuloma:

- Often asymptomatic.

- May cause pain or fractures.

- Cortical osteoma:

- Often asymptomatic.

- May cause mild pain.

However, the vast majority of good malignant tumors are actually formed by metastases that arise from other sites, the most common source being the breast in women and the prostate in men.

How does bone react to tumors?

The reaction of bone to tumors depends on the type of tumor, its location, size, stage of development, and other individual factors. In general, bone can react in different ways to tumors, whether benign or malignant.

Reaction to benign tumors

- Formation of additional bone tissue (osteoid): Some types of benign tumors, such as osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma, can stimulate the formation of additional bone tissue (osteoid) around them. This can result in the formation of an area of sclerotic bone.

- Inflammatory response: Benign tumors may cause a mild local inflammatory reaction, which can lead to symptoms such as pain and swelling.

- Cartilage formation: Some benign tumors, such as chondromas, are composed of cartilage cells and can cause cartilage tissue to form within the bone.

- Bone deformity: Depending on their size and location, some benign tumors can cause bone deformity.

Reaction to malignant tumors

- Bone destruction: Malignant tumors, such as osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing’s sarcoma, often have the ability to destroy surrounding bone. They can cause significant bone damage and weaken normal bone structure.

- Formation of new lesions: Malignant tumors tend to be more aggressive and can spread to other parts of the bone or to other bones, causing new lesions to form.

- Pathologic fractures: Due to the fragility induced by bone destruction, malignant tumors can increase the risk of pathologic fractures, where the bone breaks spontaneously without obvious trauma.

- Intense inflammatory reaction: Malignant tumors can cause a more intense inflammatory reaction than benign tumors, often resulting in severe pain and swelling.

- Compression of surrounding structures: Malignant tumors can compress nerves, blood vessels, and other nearby structures, causing symptoms such as pain, weakness, and circulation problems.

Bone’s response to tumors is complex and can vary greatly from person to person. Medical imaging, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, and MRIs, as well as biopsies, are often used to assess the impact of tumors on bone and guide the treatment plan. Treatment for bone tumors may involve surgery to remove the tumor, chemotherapy to target cancer cells, and radiation therapy to destroy tumor cells. The specific approach depends on the type of tumor, its location, and its stage.

Periosteal reaction

The periosteum is a dense fibrous membrane that surrounds the outer surface of bones. It plays a crucial role in bone growth, repair, and nutrition. The periosteal reaction can occur in response to various stimuli, including the presence of tumors.

Periosteal reaction to tumors

- Reactive periostitis: The presence of a tumor, whether benign or malignant, can trigger an inflammatory response in the periosteum, leading to a condition called reactive periostitis. This manifests as pain and tenderness over the affected bone.

- Osteoid formation: In response to certain tumors, the periosteum may respond by producing osteoid, a bone substance, in an attempt to strengthen the bone or fill a defect.

- Formation of a periosteal collar: In some cases, particularly with aggressive tumors, the periosteum may respond by forming a periosteal collar around the tumor. This collar can be visualized on medical images such as x-rays.

- Thickening of the periosteum: The presence of a tumor can cause thickening of the periosteum, which can be detected by imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) or MRI.

- Vascular reaction: Periosteal reaction may also involve an increased vascular response, with increased blood flow to the affected area.

Usefulness of the periosteal reaction

- Diagnostic indication: Changes in periosteal reaction can be used as diagnostic indicators. For example, thickening or formation of a periosteal collar can be observed on radiographs and used as an element in the diagnosis of bone tumors.

- Response to irritation: The periosteal reaction is often a protective response to irritation or stress at the bone level. This may include tumors, infections, or traumatic injuries.

- Impact on bone growth: If a tumor affects bone growth, the periosteal reaction can influence how the bone grows in response to the tumor.

- Guidance for treatment: Observation of the periosteal reaction can guide physicians in treatment planning, providing information about the nature of the tumor, its aggressiveness, and its impact on surrounding bony structures.

Type of periosteal reaction

Periosteal reactions to bone tumors can provide valuable diagnostic clues to health care professionals. These reactions can be seen on medical imaging, particularly on X-rays. Here are some types of periosteal reactions associated with bone tumors, particularly osteosarcomas, which can be benign or malignant:

- Solid reaction: A solid reaction of the periosteum may be observed as a dense, homogeneous line around the tumor. This may indicate the body’s attempt to strengthen the bone in response to a tumor.

- Onion-skin or lamellated reaction: This type of reaction is characterized by concentric layers of new periosteum formed in response to tumor growth. These layers may appear as onionskin on images.

- Sunburst reaction: The sunburst reaction occurs when the periosteum reacts by forming sunburst-like rays around the tumor. This is often associated with rapid and aggressive tumor growth.

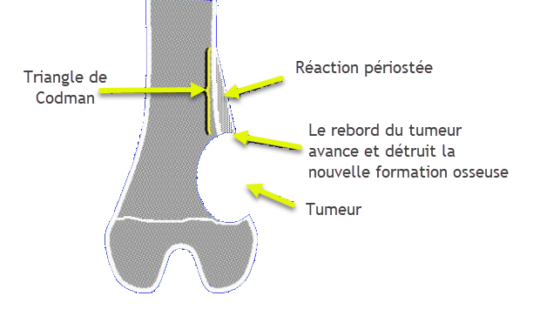

- Codman triangle reaction: This type of reaction occurs when the periosteum detaches from the underlying bone due to pressure from the tumor. This can create a triangular appearance on images, known as a Codman triangle.

Radiographic signs of bone tumor

Bone tumors may present with several radiographic findings, and the precise interpretation depends on the type of tumor, its location, and its stage of development. Here are some of the radiographic findings commonly seen in bone tumors:

- Lytic lesions: Lytic lesions appear as areas of destroyed or weakened bone. They are often seen in malignant tumors, such as osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or bone metastases.

- Sclerotic lesions: Sclerotic lesions appear as areas of bone that are denser than normal bone tissue. They are often associated with benign tumors, but may also be present in some malignant tumors.

- Delimitation of the lesion:

- Well defined: Benign tumors often have a sharp demarcation, creating a clear border between the lesion and normal bone tissue.

- Poorly defined: Malignant tumors may have blurred margins, indicating more aggressive infiltration into surrounding tissue.

- Periosteal reaction: The periosteal reaction is the response of the periosteum to the presence of a tumor. It may be solid, lamellated, or complex, providing clues to the nature of the tumor.

- Bone destruction model:

- Geographic: A geographic pattern of destruction is seen in slow-growing tumors, with a narrow transition zone between normal and abnormal bone, often in benign lesions.

- Mitted bone destruction: Multiple lytic areas scattered throughout the bone, characteristic of Ewing’s sarcoma.

- Permeable: Present in poorly demarcated lesions with a wide transition zone, such as in high-grade Ewing sarcoma and chondrosarcoma.

- Location of the lesion:

- Epiphysis: The end of the bone.

- Metaphysis: The area between the epiphysis and the diaphysis.

- Diaphysis: The middle part of the bone.

- Calcifications: Some bone tumors may have calcifications, which are visible as mineral deposits.

Bone destruction model

Geographical

The geographic pattern of bone destruction is the least aggressive, usually indicating a slow-growing lesion. The periphery may be smooth or irregular, but in both cases it is well demarcated and easily differentiated from the surrounding bone by a brief transition zone. Sometimes a sclerotic periphery of variable size surrounds the lesion. The thicker and more complete the sclerotic margin, the less aggressive the process. Benign bone tumors usually demonstrate geographic bone destruction of the bone.

Moth-eaten

The moth-eaten pattern of bone destruction is more aggressive and is characterized by a lesion that develops more rapidly than the geographic pattern. This pattern is associated with a less defined or demarcated periphery and with a more extensive transition zone between normal and abnormal bone. Malignant bone tumors and osteomyelitis may demonstrate a “mite-like” bone destruction.

Permeative

The leaky pattern denotes an aggressive bone lesion with potential for rapid growth. The lesion is poorly defined and may fuse imperceptibly with uninvolved bone sections and create a very long transition zone. Its actual size is larger than that seen on radiographs. Some malignant bone tumors, such as Ewing sarcoma, may have leaky bone destruction. Rapidly progressive osteomyelitis and osteoporosis, however, may have leaky bone destruction.

Non-aggressive lesion, solid periosteal reaction

A slow-growing tumor, such as osseoid osteoma (radiolucent nidus), causes periosteal cells to lay down bone in a continuous manner.

Type of periosteal reaction

Aggressive, lamellar or onion skin lesion

Very aggressive lesion, Sunburst

Very very aggressive lesion, Codman triangle

- Growth too fast for the periosteum

- The periosteum responds only on the edges of the raised periosteum which will ossify forming a small angle with the surface of the bone

Osteoid osteoma

Ewing’s sarcoma

Lodwick classification of lytic bone lesions

- Type 1: Geographic osteolysis : The margins have a thin transition zone and may be sclerotic or well defined.

- AI: Thin sclerotic margins. Almost always non-aggressive.

- 1B: Well-defined margins. Generally non-aggressive.

- 1C: Any part of the margin is indistinct. Aggressive.

- Type 2: Mitted osteolysis : It is difficult to define any border. Aggressive.

- Type 3: Permeative Osteolysis : The permeative pattern is characterized by multiple small holes that infiltrate the bone.

bone. This type is very aggressive and is seen in lymphomas, leukemias, and Ewing’s sarcomas. Aggressive